Python Date and Time Functions: The Complete Tutorial

Introduction

What time is it now?

That’s a pretty simple question, right? Your computer and your phone know the answer. You can probably just glance at the menu or the status bar. However, you might be surprised to learn that handling dates and times can sometimes be a bit more complex compared to simple numeric types like integers and floats. For example, how can I interpret your answer if I don’t know the time zone in which you live?

Fortunately, the Python standard library includes a few modules and classes to make it easy to work with dates and time values, whether they’re just local or include timezone information. For example, the Python datetime module provides an object-oriented interface to manipulate dates and times, including classes to represent differences in time between one event and another.

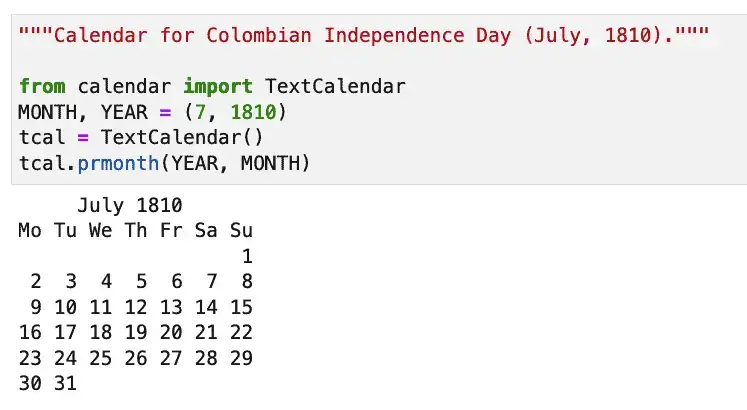

In addition to the datetime module, the timezone module allows us to work with arbitrary timezones. In contrast, the time module contains some of the functions that are useful for dealing with timezones. Finally, the calendar module lets us do some interesting things like finding out on what day of the week my birthday falls next year. (Don’t worry, you don’t have to get me anything.)

In this tutorial, we will discuss all of these modules, focusing on how to use the datetime module to work with dates and times. We will start with the basics, such as getting the current time and date in Python. We’ll show how, by default, the timezone information is not included, but we’ll also offer some easy methods for adding it on.

Then, we will move on to more advanced topics, such as working with time intervals and manipulating dates relative to the future or past. We’ll also learn how to format dates to strings and parse date strings. We’ll spend some time working on how to format and parse strings in ISO 8601 format – an international standard for representing date and time data consistently.

Note that our focus here will be on using dates and times generally, not for performance profiling. If you’re interested in Python features for profiling and benchmarking, please see How to Profile Python Code.

We’ll take it step-by-step and start with the most basic use cases first. So – if you have the time – let’s get started!

The DateTime Module: Basic Tasks

How to Get the Current Time in Python

As long as you don’t yet care about time zones, getting and displaying the current system time for the computer running the Python program is simply a matter of importing the datetime class from the datetime module and calling datetime.now().

"""Display the current local time"""

from datetime import datetime

now = datetime.now()

print(now)

The output will vary, of course, but currently looks like this:

2022-05-25 17:14:05.101025

As always with print, we see here the default string representation of a datetime object, which includes the date and time in 24-hour format, including the microseconds. We’ll get into how to format this more flexibly in a later section. For now, we’ll just point out that each of the component fields that make up this information is stored in the datetime object separately, so even given “vanilla” Python string formatting techniques, you can already do some work:

print(f"The time is {now.hour}:{now.minute}.")

Output:

The time is 17:14.

How to Get the Current Date in Python

If you’re not interested in the time, only interested in recording or displaying the current date in Python, using the datetime module’s date class is one way to get it. Instead of datetime.now(), one calls date.today() to get the current date.

# Print the current date only

from datetime import date

today = date.today()

print(today)

Output (example):

2022-05-25

The Python Datetime Module: A Closer Look

So far, we’ve used the “now” function of the datetime class to get the current time, and you may have noticed this also included information about the date. We also got today’s date by calling the date class’s "today” function. Now that we’ve touched on the very basics, it’s time to spend a little more time understanding the datetime module in more detail.

The datetime class can be thought of as the union of the fields from through other datetime module classes: date and time. In fact, we can get a date instance or an instance of the time class from a datetime instance. We can write a short program to display what each of these classes contains:

"""datetime module basic field demo"""

from datetime import datetime

# Get a datetime instance, and break it down into component parts

now = datetime.now()

now_date = now.date()

now_time = now.time()

# Show what we have:

print(repr(now))

print(repr(now_date))

print(repr(now_time))

Output:

datetime.datetime(2022, 5, 26, 7, 23, 45, 825771)

datetime.date(2022, 5, 26)

datetime.time(7, 23, 45, 825771)

Here are the names of the attributes on the datetime class and their ranges. These correspond to the output showing for the datetime class above, reading the fields displayed from left to right:

year: 1-9999

month: 1-12

day: 1 to the number of days in the month

hour: 0-23

minute: 0-59

second: 0-59

microsecond: 0-999,999

There are no surprises here. The date class component has the year, month, and day subset of fields, while the time class component has the hour, minute, second, and microsecond.

There’s another field on datetime and time that’s not shown in the output above: tzinfo. If this field is not None, it contains information about the local time zone and its relationship to UTC (Coordinated Universal Time, also known as Greenwich Mean Time).

In all the code we’ve looked at so far, tzinfo has been None. This means that so far, our datetime and time objects have all been limited to displaying time relative to the current computer’s time zone settings. How we can turn our dates and times into timezone-aware instances is the subject of the next section.

Regarding the available classes in the datetime module, we’ll focus our attention on the following classes: date, time, datetime, and timedelta. We’ve already seen three of these. The timedelta class represents time or date intervals (i.e., date and time differences).

The Python datetime module documentation has definitions of datetime.date and datetime.time that you might be interested in, especially if you work with historical dates or atomic clocks. These precise definitions are worth quoting at some length since both classes are somewhat abstracted from what we might consider their precise meanings. The datetime.date class is documented as “an idealized naive date, assuming the current Gregorian calendar always was, and always will be, in effect.” The datetime.time class is documented as “an idealized time, independent of any particular day, assuming that every day has exactly 24*60*60 seconds. (There is no notion of ‘leap seconds’ here.)”

For most of us who don’t care about dates that might have used the earlier Julian Calendar and who don’t need to figure out how to keep atomic clocks honest, as interesting as those details may be, you can safely ignore them in your Python program.

Speaking of interesting details about the Gregorian vs. Julian calendar, did you know that the first president of the United States, George Washington, had two birthdays? According to the National Archives, “George Washington was born in Virginia on February 11, 1731, according to the then-used Julian calendar. In 1752, however, Britain and all its colonies adopted the Gregorian calendar which moved Washington’s birthday a year and 11 days to February 22, 1732.”

Aware vs. Naive Datetimes

For scripts or applications that run strictly on the desktop, local time is generally sufficient. However, there’s a large number of cases where we need to provide a date or time that includes time zone information. For example:

You need to publish or save an exact date or time that an event occurred and share it outside your time zone.

You need to provide an auditing log of an event that precisely identifies when it happened, perhaps for legal or compliance reasons.

Your application runs on the web, and your users are distributed throughout the country or around the world.

For this reason, the Python documentation makes a distinction between datetime and time objects that are “aware” vs. those that are “naive”. An aware instance has valid time zone information associated with it; whereas a naive object lacks it. An aware object represents a definite instance in time; a naive object is local, and valid only in the user’s time zone. The following function can be used to tell the difference if you need to:

def datetime_is_aware(dt):

"""Returns true if the timezone is present and valid.

dt must be a datetime.datetime

"""

return dt.tzinfo is not None and dt.tzinfo.utcoffset(dt) is not None

How to Create Time Zone Aware Datetime and Time Instances

Getting the System Time Zone

Fortunately, creating instances that are time zone aware is quite easy to do in Python. Simply call the datetime function astimezone on a naive instance to return an aware datetime instance. With the function above to check our result, here’s a short example:

"""Naive datetimes vs aware datetimes"""

from datetime import datetime

dt_naive = datetime.now()

dt_aware = dt_naive.astimezone()

time_zone = dt_aware.tzinfo

print(f"dt_aware is aware ? {datetime_is_aware(dt_aware)}")

print(f"dt_naive is aware ? {datetime_is_aware(dt_naive)}")

print(repr(dt_aware))

Output:

dt_aware is aware ? True

dt_naive is aware ? False

datetime.datetime(2022, 5, 26, 18, 13, 12, 285527, tzinfo=datetime.timezone(datetime.timedelta(days=-1, seconds=72000), 'EDT'))

To get a timezone aware instance representing the current time, you first need to call astimezone on the datetime instance so that the instance itself is timezone aware, then call timetz on the result.

"""Get a timezone aware time object"""

from datetime import datetime

my_time = datetime.now().astimezone().timetz()

print(repr(my_time))

datetime.time(12, 45, 12, 544156, tzinfo=datetime.timezone(datetime.timedelta(days=-1, seconds=72000), 'EDT'))

Creating an Arbitrary Time Zone: The Zoneinfo Module

In the previous section, we created timezone-aware datetime and time instances using the astimezone method of the datetime class. This is a simple and reliable way to get the time zone of the computer the code you’re running on.

Occasionally, however, you might need to be able to create an arbitrary time zone instance. Suppose your main data center is on the Island of Guam. You’ve been asked to ensure that your web application always writes timezone-aware dates and times to the log, in Guam local time, even if you’re testing from a machine in Saluda, North Carolina.

To accomplish this you would need to step outside the datetime module we’ve been dealing with so far, and start using the zoneinfo module. The zoneinfo module’s ZoneInfo class provides a way to create time zone information objects compatible with datetime.tzinfo. You do this by passing a name we can use as a key into the IANA time zone database. (By the way, in addition to the time zone database, IANA, or Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, is the same group that maintains the root DNS zones and many other registries used in internet protocols.)

To use the database, our first task is to find a name that seems to be about Guam that we can use. We can write a short snippet of code to get a set of available names using zoneinfo’s available_timezones function, to see if we can scare up a string that will work for Guam:

"""Lookup Guam"""

import zoneinfo

for info in zoneinfo.available_timezones():

if "Guam" in info:

print(info)

Output:

Pacific/Guam

Well, that worked well, let’s write some exploratory code to make sure we’re on the right track:

tz_guam = ZoneInfo("Pacific/Guam")

print(repr(tz_guam))

# Given a datetime object, we can also look at Guam's offset from UTC:

print(tz_guam.utcoffset(datetime.now()))

Output:

zoneinfo.ZoneInfo(key='Pacific/Guam')

10:00:00

OK, that makes sense, Guam is out in the Pacific north of eastern Australia, so the clocks run ten hours ahead of UTC (Greenwich, England).

Let’s see how it compares to our machine in Saluda, North Carolina. In the example below, we see astimezone used as we’ve already used it, to get the local machine’s time zone into a datetime instance, but we see we can also use it to set an arbitrary timezone on the resulting datetime. That’s a subtle point that’s worth noting. It’s not an easy design to remember, perhaps, but it makes the code very concise.

# Get the current time, using the machine's local time zone (Eastern Daylight Time)

now_here = datetime.now().astimezone()

now_guam = now_here.astimezone(tz_guam)

print(repr(now_here))

print(repr(now_guam))

Output:

datetime.datetime(2022, 5, 27, 17, 31, 53, 744449, tzinfo=datetime.timezone(datetime.timedelta(days=-1, seconds=72000), 'EDT'))

datetime.datetime(2022, 5, 28, 7, 31, 53, 744449, tzinfo=zoneinfo.ZoneInfo(key='Pacific/Guam'))

Alright, let’s see. It’s 5:31 PM on May 27th here in North Carolina, and in Guam, it’s already tomorrow at 7:31 AM. Currently, Eastern Daylight Time is UTC-4, and we learned earlier that Guam is UTC+10. Sure enough, 7:31 AM tomorrow is 14 hours ahead of 5:31 today.

With the Guam time zone as a module constant somewhere, our routine to get a current time object for the log (always relative to Guam), is quite simple:

# Get the current time in Guam:

from datetime import datetime

from zoneinfo import ZoneInfo

TZ_GUAM = ZoneInfo("Pacific/Guam")

# ...

def guam_now():

return datetime.now().astimezone(TZ_GUAM)

That turned out to be super simple, but we should make a mental note to ask the boss how our data centers ended up in Guam.

Getting a Future Date or Past Date in Python

So far we’ve been incredibly zen in our approach to dates and times: we live always in the present moment. Yes, we seemed to get a time in the “future” when Guam was fourteen hours ahead of us, but no, that was just “right now” in another time zone.

Using a Date or Datetime Constructor

To construct future dates or datetime objects, we simply pass the fields we discussed earlier into the appropriate constructor. For datetime, we can specify the tzinfo field if we wish, and we have to pass the date fields (the time fields are optional).

# Using the date and datetime constructors

from datetime import datetime, date

from zoneinfo import ZoneInfo

independence_day = date(1776, 7, 4)

# A date that will live in infamy:

pearl_harbor = datetime(1941, 12, 7)

pearl_harbor_more_exactly = datetime(1941, 12, 7, 7, 55, tzinfo=ZoneInfo("Pacific/Honolulu"))

print(independence_day)

print(pearl_harbor)

print(pearl_harbor_more_exactly)

Output:

1776-07-04

1941-12-07 00:00:00

1941-12-07 07:55:00-10:30

That “-10:30” part of the last line is the offset for Hawaii from UTC, ten and one-half hours (according to IANA, at least). Most of the other documentation I’ve seen shows it should be -10:00.

See the next section for another way to get past and future dates.

Manipulating Dates and Times With Timedelta

How to Add Days to a Date Object In Python

Besides using a constructor, we can use the datetime module’s timedelta class to get an arbitrary date or time in the future or the past. The timedelta class represents the difference between two dates or times. For example, let’s say you’re a library writing a custom application to track when a book will be due. You can add fourteen or twenty-one days to today’s date, and easily get the resulting date.

You generally construct a timedelta object using either days or seconds as a value. (You can also use both). Either value can be positive or negative. Here are some timedelta examples:

"""Constructing a Python timedelta object"""

from datetime import timedelta

# 22 minutes from now

td1 = timedelta(seconds=22*60)

print(td1)

# 14 days ago

td2 = timedelta(days=-14)

print(td2)

# 46 hours from now (2 days minus two hours)

td3 = timedelta(days=2, seconds=-60*60*2)

print(td3)

Output:

0:22:00

-14 days, 0:00:00

1 day, 22:00:00

With that knowledge, we can easily write our simple library due-date program:

"""Using timedelta to calculate a due date"""

from datetime import timedelta, datetime

LOAN_PERIOD_DAYS = 21

today = datetime.today().date()

due_date = today + timedelta(days=LOAN_PERIOD_DAYS)

print(f"Today is {today}. Your book is due on {due_date}.")

Output:

Today is 2022-05-28. Your book is due on 2022-06-18.

Adding or Subtracting Time

The same technique can be used to apply a time difference, too, of course. And remember we can always move dates and times ahead as well as behind.

There is a caveat when adding or subtracting times. Unlike adding or subtracting date objects, which we saw above uses simple math operators, in the case of datetime.time, the + and - operators are not overloaded. So time intervals can not be added or subtracted on time objects. So the way you have to do it is to add or subtract the time interval you want to the datetime object first, then use the datetime object’s time function to return just the time if that’s what you want.

# Travel 3 minutes into the past:

from datetime import datetime, timedelta

MINUTES_AGO = 3

now = datetime.now()

earlier = now - timedelta(seconds = MINUTES_AGO*60)

print(f"Now it's {now.time()}. Three minutes ago it was {earlier.time()}. See you there!")

Output:

Now it's 16:11:11.562711. Three minutes ago it was 16:08:11.562711. See you there!

Again, we’ll focus on getting some prettier formatting going in a later section. For now, let’s continue our discussion of the Python timedelta class.

Finding the Difference Between Two Dates

So far we’ve looked at how to construct a timedelta object using either days or seconds and use it to adjust a date into either the future or the past. So we’ve seen basically this formula at work (pseudocode):

datetime_1 +/- timedelta == datetime_2

If this were simple algebra, it would also stand to reason that we could move terms around to get something like:

datetime_1 - datetime_2 == timedelta

So you might be wondering, “Does that also work in Python?” The answer to that question is that it sure does, and we can use this property to implement behavior such as a countdown timer or calendar.

Calculate Remaining Days Until Christmas in Python

Now that we know that subtracting dates or datetimes will return a timedelta object, let’s work a fun program with it.

If your kids need to know when Santa will be here, here’s how you could do it. (Apologies in advance to those who don’t celebrate that particular winter holiday, but feel free to adapt the code!).

ou’ll notice we’ll also do a datetime comparison in this program; we’ll explain it all after showing the code.

from datetime import date

def get_christmas_year(today: date):

"""The next Christmas will usually be this year, but not between Christmas and New Year's"""

year = today.year if not (today.month == 12 and today.day > 25) else today.year + 1

return year

today = date.today()

christmas = date(get_christmas_year(today), 12, 25)

days_till_christmas = christmas - today

print(f"Today is {today}. Christmas is {christmas}, which will be in {days_till_christmas.days} days.")

Since this code is more important than the usual code I post (ask anyone under 12 years old), we’ll depart from the our usual formatting practice a bit and show the results as of today from repl.it.

Formatting and Parsing Dates and Times in Python

If you’ve been reading through the article so far, you may have noticed that many of our “output” sections have been rather ugly. For example, in our section on “Adding or Subtracting Time”, the output from one of our examples was this:

Now it's 16:11:11.562711. Three minutes ago it was 16:08:11.562711. See you there!

Fortunately, by digging into the datetime module a bit more, we can improve on this quite a bit.

The classes in the datetime module have two important functions, strftime and strptime. At a high level, those functions can be described as follows:

strftime is an instance method on the date, time, and datetime classes. Its purpose is to convert the object to a string using special formatting codes that allow much more precise control than the default format from __repr__ or __str__.

strptime is a class method, so you don’t need an object instance. It is only defined on the datetime class. Its purpose is to be able to flexibly parse a string to a datetime instance. As we’ve already seen, from there you can, if desired, obtain simply the time or date portion as a date or time instance.

As a Python programmer, you may find those names a little bit more compressed than what you’re used to. The names actually come from the same functions in C, the language on which Python is based. Their shortness reflects the fact that, prior to the 1989 ANSI C standard, some C compilers only supported identifiers up to eight characters in length!

Strftime and strptime share the same formatting codes. As with everything in Python, however, the best way to get a feel for them is by coding up several examples.

Formatting Dates and Times with Strftime

We’ll start with some formatting examples with strftime. Since we’ll need a date and time for the example, I’m going to choose a day that’s special for me, narrow the time down as much as I can, and throw a Hail Mary pass on the microseconds.

So here we go:

from datetime import datetime

from zoneinfo import ZoneInfo

california = ZoneInfo("America/Los_Angeles")

special_day = datetime(2011, 10, 1, 10, 45, 0, 123456, tzinfo=california)

# Get the sub-objects, or we could have used the original datetime

# instead for these examples

special_date = special_day.date()

special_time = special_day.time()

# What day of the week was John's special day?

# Please not Monday... Please not Monday...

print(special_date.strftime("%B %d, %Y was a %A."))

# %I lets us work with a 12 hour clock

# %p gives us AM or PM equivalent in our current locale.

# What time was our big event?

print(special_time.strftime("The big event took place around %I:%M %p."))

# More fun facts

print(special_day.strftime("In terms of %Y, %b %d was day number %j."))

# Where was it?

print(special_day.strftime("The event took place in timezone at UTC%z."))

Output:

October 01, 2011 was a Saturday.

The big event took place around 10:45 AM.

In terms of 2011, Oct 01 was day number 274.

The event took place in timezone at UTC-0700.

Strftime Formatting Codes Review

Let’s review the formatting codes we used to get these four lines of output (lines 14, 19, 22, and 25).

For line 14:

%B The full month name for the current locale.

%d Day of the month, zero-padded to two digits. (We’ll show how to get rid of the zero-padding below)

%Y Four-digit year.

%A Full day of week name for the current locale.

The issue of strftime and strptime not having a one-digit day of the month code is easily fixed at least on the output side by mixing in a little modern f-string magic. I found it easy to mix f-strings and strftime format strings, at least in this case:

"""Mixing f-strings and strftime format strings"""

# Output: October 1, 2011 was a Saturday.

print(special_date.strftime(f"%B {special_date.day}, %Y was a %A."))

For more on Python f-strings, see Python Format Strings: Beginner to Expert.

Continuing our review of the format codes we used, on line 19:

%I Hour, zero padded to two digits if need be, beginning with 00 for midnight.

%M Minutes, zero padded to two digits.

%p Equivalent of “AM” or “PM” for the current locale.

By line 22, we’re starting to repeat ourselves a bit, but the new format codes here are:

%b Short name for month (recall that we used %B for the full name above). In English, short names are “Jan”, “Feb”, etc.

%j Just for fun, the number of the day in the year. I say “just for fun because you probably won’t need it often.”

Line 25 contains only one code, a UTC offset, a precise value beginning with +/-HHHH, e.g. -0700 (seven hours behind), +1030 (ten and a half hours ahead), etc.

Parsing Dates and Times with Strptime

The Python datetime class has a static method, strptime, that can be used to flexibly parse datetimes. It accepts a two arguments, a string representing a date, and a format string representing how to parse it. The format strings are compatible with strftime, however, strptime will set some defaults if parts of a full datetime are not available, as follows:

If you pass a format string that will only retrieve the time portion, the date will be set to January 1, 1900.

If you pass a format string that will only retrieve the date fortune, the time will be set to the earliest date possible on that day (i.e. midnight, or 00:00).

From what I’ve seen, it’ll also select defaults in other positions, for example, only an hour will set the minutes to zero, but I haven’t tried every possible combination.

A simple example can show strptime in action.

"""Simple strptime example"""

from datetime import datetime

date_string = "Saturday, October 01, 2011"

format_string = "%A, %B %d, %Y"

parsed = datetime.strptime(date_string, format_string)

date_string2 = parsed.strftime(format_string)

print(date_string)

print(date_string2)

print(parsed)

Output:

Saturday, October 01, 2011

Saturday, October 01, 2011

2011-10-01 00:00:00

In this example, we demonstrate the compatibility of strptime and strftime by reading a datetime from a string using strptime formating (at line 7), and parsing the datetime back out to a string using the same format string (line 8). On lines 10-12, we show the strings to show that they’re identical, then display the datetime using the default format.

Saving and Parsing Dates in ISO 8601 Format

The datetime module provides limited support for formatting and parsing dates in ISO 8601 format. For example, the datetime class can format a string to ISO 8601 format using the isoformat method. The fromisoformat can parse such a string back to a datetime object, however, the Python documentation warns against using it to parse arbitrary ISO 8601 strings that weren’t created by the isoformat. (For those use cases, it recommends using the third party module, dateutil, which we’ll discuss below).

Meantime, since the datetime library in core Python is fine if you control both the strings created and the parsing side, let’s show a quick example:

"""datetime ISO format handling demo"""

from datetime import datetime

from zoneinfo import ZoneInfo

california = ZoneInfo("America/Los_Angeles")

special_day = datetime(2011, 10, 1, 10, 45, 0, 123456, tzinfo=california)

# Format

string = special_day.isoformat()

# Parse

dt = datetime.fromisoformat(string)

print(string)

print(dt)

Output:

2011-10-01T10:45:00.123456-07:00

2011-10-01 10:45:00.123456-07:00

Dateutil: A Python Third-Party DateTime Library

Dateutil is a powerful and popular third-part extension to the Python datetime module. It is mentioned several times in the Python standard library documentation on datetime.

Like almost all third-party libraries, you can install it using pip.

pip install python-dateutil

Some of its main features are:

More flexible ISO 8601 date parsing than the standard library

datetime.fromisoformatfunction.Another flexible parser that can “understand” many non-standard date formats, with some very intelligent defaults.

A

relativedeltaclass that lets you specify time differences in many ways that are easier to use and more “calendar-aware” than datetime.timedelta.A recurrence rule class (

rrule) that can be used to schedule a series of events as you might see in a calendar application like Google Calendar or Outlook.

In general terms, the difference between Python’s datetime module and the third-party dateutil module is that datetime tends to do things in a way that is explicit and precise, but less flexible and less “calendar-aware”. The dateutil module, in contrast, is generally more flexible and can do things less explicitly (in the case of parsing), using somewhat more useful defaults for some values.

Let’s take a look at a few of the classes provided by the dateutil module to get a feel for them in action.

Dateutil’s General Date and Time Parser Class

In our discussion of Python datetime’s strptime function, we showed how strptime could be used to parse dates and times using format strings that are compatible with those used in strftime. Having to provide the format codes explicitly gives precise control over how a date gets parsed, but in contrast, the dateutil.parser module does an excellent job of parsing arbitrary dates without a formatting string. Simply pass the string containing the date or time to the parse function, and most of the time, it will do the right thing.

In the following code, we show today’s date. We then use a list of date strings, and pass each one to “parse”, building a table of the examples and the resultant parsed datetime object. The core of it (boiled down), is:

from dateutil import parser

# ...

parser.parse(...)

"""Demonstrates dateutil's flexible parse method"""

from datetime import datetime

from dateutil import parser

print(f"Today is {datetime.now().date()}\n")

examples = ["December 7, 1941", "2010-05-22", "10:22 AM",

"Wednesday at 4:00 PM"]

print(f"{'EXAMPLE: '}{'PARSED:' : >21}")

print("------------------------------------------")

for example in examples:

parsed = parser.parse(example)

print(f"{example : <22} {parsed}")

Output:

Today is 2022-05-31

EXAMPLE: PARSED:

------------------------------------------

# Python Date and Time Functions: The Complete TutorialDecember 7, 1941 1941-12-07 00:00:00

2010-05-22 2010-05-22 00:00:00

10:22 AM 2022-05-31 10:22:00

Wednesday at 4:00 PM 2022-06-01 16:00:00

Looking at the table of output, the first two lines are interesting to the extent that they are very different date strings, and the parse method handled them both without an explicit format string to tell it what to do. The third line of the table shows that – unlike strptime – time strings without date information are interpreted to be a time happening today, which is probably a much more reasonable default for what most of us mean by “at 2:30”, for example. In the final line, We see Wednesday at 4:00 PM gets interpreted to mean “the next Wednesday relative to today”, which in this case is June 1st (tomorrow, as I run this).

This is a very nice result for a parser where we don’t need to specify a format string upfront for every possibility. The tradeoff for this convenience is that such a parser probably takes more clock cycles to run than strptime, so it may not be a great fit for parsing a large series of values in a known format.

Smart Relative Date/Time Offsets with Dateutil’s Relativedelta

As we’ve seen in an earlier section, Python’s datetime module has a timedelta class that allows us to specify a time offset, generally either in seconds or days. This is useful in some cases, but consider the case where you want two months from now to map to the same date of the month, or the “end of the month” if you call it on the 31st. Doing that manually using days would require a table of months to days in the month, knowing about leap years, etc.

Here again, the dateutil module provides a solution that’s far more flexible. In the code below, for example, we use the relativedelta class to calculate some date offsets in terms of weeks and months.

"""Using dateutil's relativedelta class"""

from datetime import datetime

from dateutil.relativedelta import relativedelta

today = datetime.now().date()

one_month_from_now = today + relativedelta(today, months=1)

six_weeks_ago = today + relativedelta(today, weeks=-6)

print(f"Today is {today}.")

print(f"One month from now = {one_month_from_now}.")

print(f"Six weeks ago was {six_weeks_ago}.")

print(f'Today is a {today.strftime("%A")}, six weeks ago was a {six_weeks_ago.strftime("%A")}.')

Output:

Today is 2022-05-31.

One month from now = 2022-06-30.

Six weeks ago was 2022-04-19.

Today is a Tuesday, six weeks ago was a Tuesday.

Handling Recurring Events With Dateutil’s Rrule (Recurrence Rule)

For our last DateUtil example, let’s take a look at how we might code a series of recurring events, similar to what you might do when you schedule a repeating meeting in Outlook:

"""dateutil example, repeating an date five times beginning with today's date"""

from datetime import datetime

from dateutil.rrule import rrule, WEEKLY

today = datetime.now().date()

days = rrule(WEEKLY, dtstart=today, count=5)

for day in days:

print(day.strftime("%B %d, %Y"))

Output:

May 31, 2022

June 07, 2022

June 14, 2022

June 21, 2022

June 28, 2022

Closing Thoughts

As we’ve seen, the Python ecosystem contains a number of built-in and third-party classes that make date and time handling convenient and reliable. We hope the many examples in this tutorial have given you some ideas that you can use right away in your code!